Originally posted on theguardian.com

The interactive documentary gives a brief introduction to the first world war through a global lens. Link to video

Telling the story of the first world war with 2014 technology. By Francesca Panetta.

On July 2014, we launched our most recent multimedia interactive to coincide with the 100-year anniversary of the first world war.

It’s a summary of the war, but with a global twist: stories from the outbreak of war to its aftermath are told through the voices of 10 historians from 10 different countries.

It is available in seven languages: English, French, German, Spanish, Italian, Hindi and Arabic. We are also inviting our readers to translate the project into even more languages for relaunch in the autumn. In fact, if you want to get involved, please email us!

Photograph: Guardian

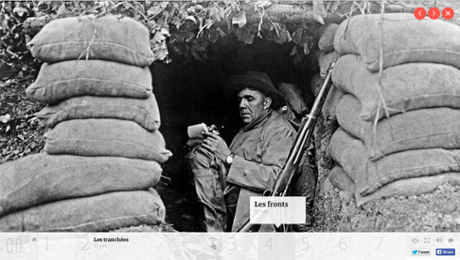

The documentary is told through seven chapters: each opens with a video and ends with an interactive, providing an opportunity to dig deeper into the stories introduced in the videos. Within the interactive maps there is fresh writing, picture galleries, extended interviews from the historians and articles from the Guardian’s archive. So after first watching the brief introductory film you can then spend up to three hours in further exploration.

The making

We aimed to create a beginner’s guide to the first world war, but with the quality of journalism that the Guardian prides itself on. A cross-media piece seemed to be an ideal treatment for a richly emotional experience as well as a technically accurate and detailed story. The films allow to get to the emotional heart of the story immediately – essential for non-experts. Once we have interested users, the idea is that the interactive guides can provide depth.

Photograph: Guardian

I started by interviewing the historians from around the world. I was determined to give a global take on the war. As a child, I learned about this war from a very British perspective. But I wanted our introductory guide to be more international in both content and feel. That approach chimed with the Guardian’s editorial ambition: to be a global liberal voice.

So we found 10 historians from key regions involved in the war and allowed them to tell their stories of the war, with their own perspectives and accents. I also sourced letters, diary entries and poems from around the world. We’re familiar here in the UK with war poets Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon, but I thought there must be Turkish and Indian equivalents. With the help of Modern Poetry in Translation we found poems from all over the world. Of course, cutting all this together is itself editorialising. But as much as possible we wanted this global story to be told through the words of participators rather than a posh, English, scripted voiceover!

Once the backbone of the narratives was arranged in audio, our executive film producer Lindsay Poulton got to work. She and her team of researchers and producers searched through hours of archive film footage and stills. We worked with the Imperial War Museums for this project and they have a vast archive, most of which you can view online. We also scoured Getty, Corbis and Pathé. With all of this footage they were seeking to immerse the viewer in the sights and sounds of war. This was not a place for reconstructions.

Photograph: Guardian

In parallel, we were working with Kiln, an amazing team of interactive designers, developers and journalists. We spent some time working out the concept – what this thing would actually be. We asked why we needed all the different kinds of media, and what the story we were trying to tell was. Weren’t the films enough? Why bother with the interactive too?

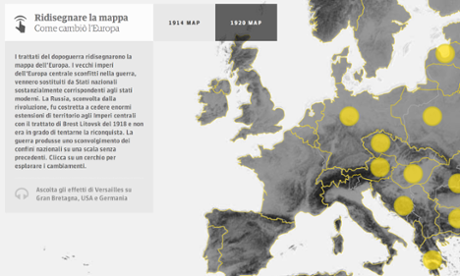

Once Kiln started building the technology in April, the interactive design developed. For interactive 5 Kiln visualised their data to show the death-toll numbers around the world – a key detail that when rattled off by a historian quickly in a film can be hard to absorb. In interactive 6, Kiln laid the 1920 postwar map of the world over the 1914 prewar version. It’s complicated – something you need to take your time over.

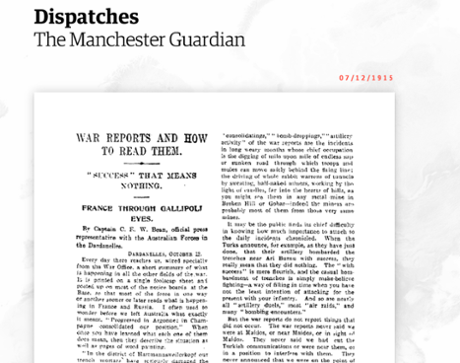

The Guardian archive articles from the time were dug up by our research team and our feature writer Stephen Moss started to write the copy.

Photograph: Guardian

Once we had all the content and had established that the interactive was working, we had it translated into multiple languages by professional translators at Business Languages Services. Kiln designed a clever mechanism that displayed the subtitles and an international team of Guardian journalists checked them for accuracy. We had all languages skills in-house, except Hindi! The Guardian has never before made a large-scale project like this available in so many languages, and it was far from easy. But opening up this story to our users around the world seems worth the effort.

Inevitably there were bumps along the way. One of the most challenging aspects of these multimedia interactives was accounting for all the hundreds of devices that our users will view this on and the variations in the speed of their internet connection. We built an innovative detection system that will help to serve the most suitable file-sizes and and the highest possible image resolution while maintaining a smooth experience. We also have a team of people methodically testing the strength of the interactive. But as hardware and software change so quickly it is not an exact science. It is a set of compromises.

Photograph: Guardian

Strategy

This first world war project is intended to be a resource to the public. This is the first time we have ever offered up such an ambitious project up in so many languages and it comes under the area of innovation which I’m responsible for as the Guardian’s special projects editor.

We’re lucky at the Guardian that we have such a big audience online – now more than 100 million unique browsers a month. It means our website is our main stage. For a storyteller, that’s exciting, because digital is an open space with endless possibilities in terms of treatment and format.

The large pieces I’ve created over the last few years include View from the Shard, Firestorm, The Shirt on Your Back and Digital Sins. In all these cases we experimented with form, using film, words, pictures and audio in new ways, to push forward what the Guardian can do.

I often get asked where all this will go and my answer is always the same: technology is at the steering wheel, but there is always going to be a demand for great content. If we can be creative and fleet of foot enough to stay ahead of the game, then as an organisation we will develop and thrive. This is what the Guardian has always done – been brave – and innovations in digital storytelling is part of that strategy.

0 comments