What is Motto? Is it a film? A video game? An interactive book? A visual poem? A treasure hunt? A philosophical treatise? A work of fiction? A documentary? Contemporary art? It’s all of that and none of that. Motto is a strange object, an unclassifiable curiosity at a time when digital creations are mainly reduced to web series and virtual or augmented realities. This “adventure that reaches through walls,” in the words of its creators, is the story of a ghost named September, the narrator’s friend.

The experience takes place on the Internet exclusively on mobile devices. Users are invited to participate from their own environment and their own “reality” by recording short videos that will fuel the adventure, interweaving with thousands of other tiny videos gathered from all over the world.

Motto is an unidentified digital object that can’t be reduced to a genre or a school. A National Film Board of Canada (NFB) production, Motto is the work of Vincent Morisset’s digital creation studio, AATOAA, in collaboration with Montreal novelist Sean Michaels. The NFB-AATOAA team has a proven track record with 2011’s BLA BLA, “a film for computer” and 2015’s Way to Go, an “interactive forest walk” accessed on a computer or via a virtual reality headset. Here’s a look back at the three years of work that brought Motto to our pockets.

1. At the beginning

To grasp the creative issues Motto explores and understand the process that lead to the final experience, we must go back to the beginning. Vincent Morisset has the reputation of being reticent when it comes to putting his intentions, script notes, or directing choices down on paper. For good reason: AATOAA likes to keep the doors and windows wide open. They don’t make choices based on a priori assumptions, preferring to give free rein to experimentation and testing things out—guaranteeing beautiful discoveries (and, inevitably, small disappointments). “He finds what he’s looking for as he goes,” says NFB producer Marie-Pier Gauthier, “and that’s what’s so appealing about his work. We’re receptive to his artistic approach. We’d rather have a good idea at the outset that asks a lot of questions than ready-made solutions, a creative process without any surprises.”

Challenging the gaze

That said, there are, of course, foundations, intuitions, and inspirations. “I’d like to explore the notion of meaning-making,” wrote Vincent Morisset in his very first working document, “How the brain connects the dots, reads between the lines, makes associations.” He then sketched out a possible form: “An impressive amount of visual content, an algorithmic structure that ties these things together, and an interactive process that allows us to evolve through this flow of images and sounds. I’d like to explore an approach that’s closer to the documentary process through a collection [of images] that both I and collaborators make (online and in the field). The uncontrolled nature of the documentation process and the random aspect of the assembly will be confusing, fascinating, and surprising, ultimately leading to moments of grace.” The goal has been defined, the artistic intentions set. Now they just had to find the best way to get there.

The idea behind the project is the desire to challenge our gaze, to question and expand how we see things, and to change our perceptions with the use of images coming from all directions. Between the lines, we can sense the quest for a new interactive experience. Something that has never been done before. Something that doesn’t exist anywhere else. Something that will shake audiences up. Something that will move them.

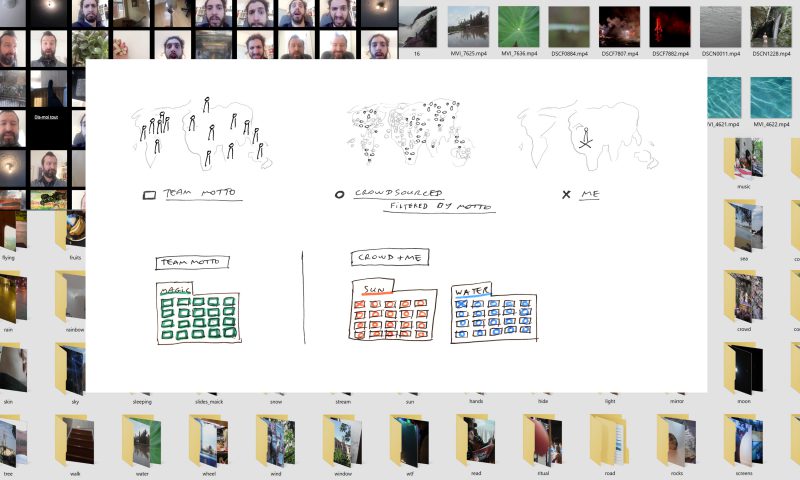

Early sketch of content sources (videos from the creative team, the other participants and the reader)

Taking the time to think

AATOAA’s venture into new territory—and out of their comfort zone—stems from the possibilities that subtend the creative process. First of all, there’s the use of mobile devices. Vincent Morisset writes: “With a unique filming process and democratized technology, we want to arrive at a collection of perspectives and moments that we never or rarely see on screen.” Today, you can record images anytime and anywhere thanks to your phone, that small mass of technology that’s an extension of your eyes and hands. How does a creator convert our constant ability to film into a creative and participatory act? How do they turn users into gleaners of images, images that take on their full meaning through this project? Motto is inspired by the work of Agnès Varda, along with Snapchat, Italo Calvino, Christian Marclay, W. G. Sebald, the film Being John Malkovich, and the website astronaut.io.

In addition, the creators wanted to explore editing video-snapshots collected with users’ smartphone cameras, to cultivate the “power of the spaces in between,” as Vincent Morisset writes. “From the outset, we were thinking of inviting as many people as possible to make small videos, intuiting that we could create links and comparisons between them,” explains Caroline Robert, the editor of Motto. Inspired by the famous Kouleshov effect, the team envisioned this project as a huge game of cards, drawn at random and juxtaposed to create new meanings not contained in the individual images. In short, 1+1=3. The idea is that playing with a more or less random assembly of images might give rise to a fragile and precious form of poetry. What’s more, by relying on serendipity, hypertext, and non-linearity, the process embraces aspects of the fundamental nature of the web that are dear to Vincent Morisset.

“The camera becomes our interface and our mode of interacting.”

-Vincent Morisset

At a time when social networks are growing at an ever more frenetic pace, of widespread zapping and endless scrolling, of ultra-short messages and ephemeral videos, the project is an invitation to slow down and to take the time to think. In Way to Go, AATOAA invited us to take a walk in a mysterious forest, to go slowly enough to explore, discover, and familiarize ourselves with the potentially wondrous world hidden by the side of the road that we have to stop to really see. “No one’s waiting, no one’s keeping score,” we were told as we stood at the edge of the woods. With Motto, the creators have adopted a similar approach with the slow web. “The project challenges Internet time as we know it and consume it,” says Marie-Pier Gauthier. In fact, Motto’s attention economy is closer to that of a book than to that of Twitter.

2. Finding the right form

Through what is called a “study phase,” the NFB gives creators the chance to develop their ideas, push their thinking further, and dive deeper into a project. Motto’s study phase took place between December 2017 and March 2018, giving them the time to bounce all kinds of ideas off each other.

Time to explore

The AATOAA trio “works telepathically.” Programmer Édouard Lanctôt-Benoit’s role was to dip his hands into the digital sludge to extract a few treasures. To find gold nuggets in his sieve, he had to cast a very wide net—meaning many tests, trials, and prototypes. Motto’s “toolbox” was built, little by little, by keeping some things and discarding others. But the editorial constraints of the project—the direction, the mechanics—were above all what guided the technological choices at the outset.

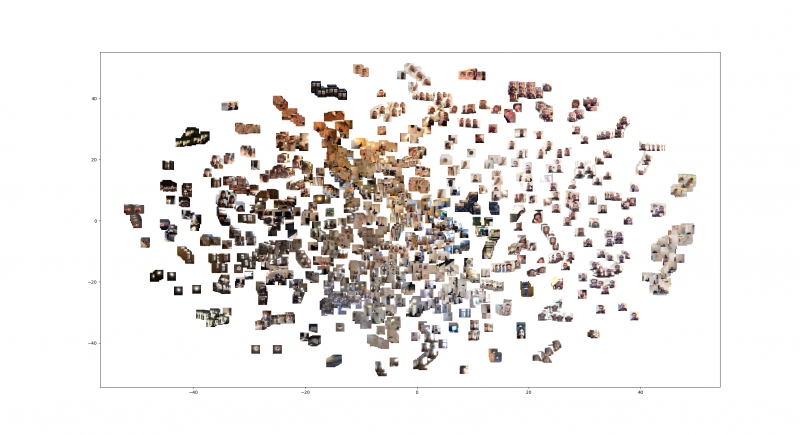

Their initial experiments revolved around artificial intelligence (AI), combining computer vision and automated machine learning of images. They conducted video analysis with software able to identify shapes, gestures, or objects. They explored facial recognition to identify faces in the images. As advanced as artificial intelligence is, it didn’t seem to suit the ambitions—or the DNA—of the project. “AI is interesting because it’s still imperfect today,” explains Vincent Morisset. “It opens up new possibilities, but we weren’t able to find as many ‘moments of grace’ as we had hoped for during our experiments. In 80% of the cases, it was too banal or just not interesting enough. Poetry remains a very human trait…”

Facial recognition, for instance: Édouard Lanctôt-Benoit realized that it was not supported by small, lower quality smartphone videos where close-ups and wider shots were mixed in together. He had to dig deep and get creative, bending the potential of machine learning to the needs of the project. Similarly, the computer vision tests weren’t entirely in vain either: when used as an interactive tool, real-time analysis of images lets the creators ask users to carry out small actions (turn around, put your hand in front of the camera) and for the platform to respond to them as soon as they’ve been carried out. The team ended up keeping this tool, which reflects their desire to develop a new form of interactivity.

At the same time, AATOAA was carrying out the first assembly tests and many other experiments that kept the team busy for almost a year. A trace of this work remains in the final project: the special effects below inspired Motto’s overall structure and aesthetics.

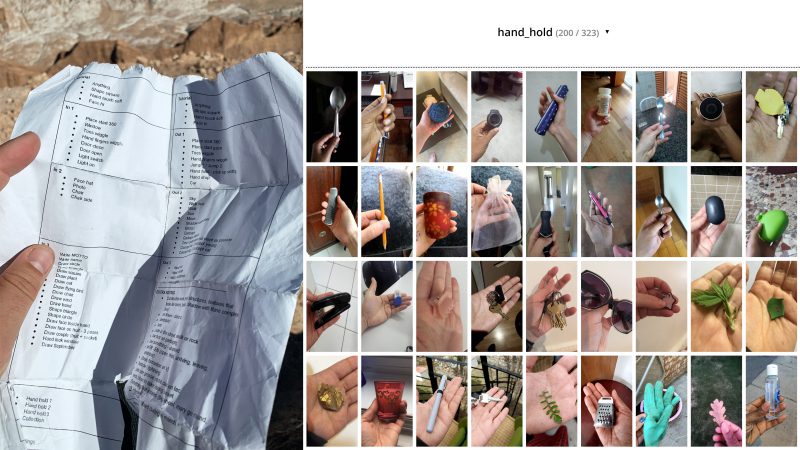

The search for raw materials

Perhaps, as the French say, the best soups are made in old pots—meaning that sometimes the old ways of doing things are best.

The desire to provide a mobile, crowdsourced experience is a bold move. If you’re not careful, the jumble of collected images can quickly turn into audio-visual mush. So, as in any good recipe, it’s important to measure the ingredients correctly or the sauce won’t take. Interestingly, annotating videos by keywords, however rudimentary that may seem compared to the advanced digital technologies available today, lets the videos be edited together in a compelling way.

But to test the potential of intelligent and algorithmic editing, you first have to build up a sufficiently vast bank of images. The image bank began with the personal archives of Vincent Morisset and Caroline Robert, the visual artist of the AATOAA trio. It was then expanded by searching the Internet—and YouTube in particular—for temporary clips that will be gradually replaced by Motto user content. In particular, the team sought beauty in the banality of everyday life—household waste included. These images were then categorized with labels such as “animals,” “hands,” “sky,” “dance,” “places,” “road trip,” and so on. Caroline Robert also classified them according to more abstract concepts, such as “beauty,” “loneliness,” or “endings.” Using the tools developed by Édouard Lanctôt-Benoit, these families of apparently unrelated videos can then be summoned and replayed like words manipulated to form sentences.

The first bank then had to be completed with expressly sought images before Motto users would start contributing their own footage. Marie-Pier Gauthier explains: “One of the difficulties of the project is the amount of content it requires. We had to limit ourselves because it wasn’t possible to buy audio-visual material from all over the world. As producers, we never veto ideas, but we do have budgetary imperatives to respect.” With a little imagination and ingenuity, the team found images at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa (rock and plant collections and a horse skeleton) and at the Neues Museum in Berlin (the bust of Akhenaten). They also set off on an expedition to Chile… but more on that to come.

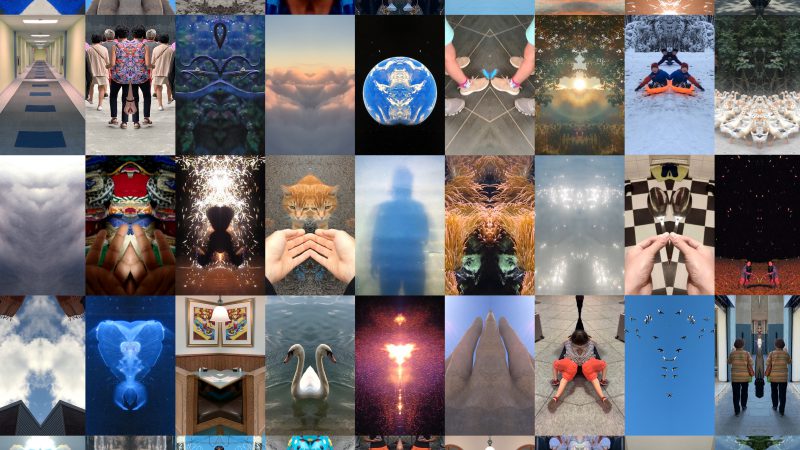

Pareidolia is another old pot that can be used to make a good soup. Pareidolia is our tendency to see or recognize faces and objects in cloud formations, smoke, stains, a landscape, or a pebble. To trigger it, the Motto creators decided to regularly use a split screen mirror effect: the screen is cut in half with the image reflected on both sides, engaging the user’s imagination to see something other than what the image formally designates. “This mirror effect in the videos is like doors opening or passageways to another world—to September’s world. We also use it as a chorus or as a theme song before each new chapter,” notes Caroline Robert.

The technological challenge

The team faced a final challenge: the platform must work perfectly anytime, anywhere, and on most smartphones. Adapting to different devices meant designing multiple paths for the same result, and not burning any phones in the process! It was a big challenge: “All users need to be able to film images, save them and send them to our server. We then need to be able to add text and special effects and ensure that the result is the same, whatever the mobile device,” explains Édouard Lanctôt-Benoit.

The programmer continues: “The interface must be as fluid as possible, with few user prompts. You need to be able to understand it without a tutorial. The aim is for everything to be magical. It has to work so well that people focus on the experience and not the technology. The technology has to be forgotten; that’s what our work is all about.” It’s important to note that Vincent Morisset did not choose an app and preferred to make Motto accessible from the web browser of a mobile device at the motto.io address “because it’s free, instantaneous and I’m a lover of the web and open and free platforms.”

All of these technological developments unfolded like an ongoing game of ping pong between the creators. They prototyped, tested, and evaluated. They went forward with some ideas and pulled the plug on others—ongoingly involving the whole AATOAA team, along with a newcomer for the occasion: Montreal novelist Sean Michaels, author of Us Conductors and The Wagers.

Take your phone

Go to motto.aatoaa.com

Film what you see without embellishment

Frame the subject

Be succinct

Try things

Be yourself

-Vincent Morisset for Motto

3. Finding the story

With the overall form in place, the question became one of how do you push it further? The images would constitute an “impressionist patchwork,” a blank canvas and a visual poem of sorts, but should a narrative with a beginning, a middle and an end, come into play? And if so, how? How could Motto become a story that is deeper and more exciting than a mere accumulation of images?

Working with words, and with a literary writer, at this stage in the development of a project was a first for Vincent Morisset. He had known Montreal writer Sean Michaels for a long time: the two had previously collaborated on the 2008 documentary Miroir noir about the band Arcade Fire and, more recently, on the accompanying texts for Way to Go. Given that they come from very different worlds, their collaboration was a daring gamble.

Sean Michaels embarked on the project in April 2018, after the team had been at it for about a year and just prior to the development phase. At this stage, the creators had begun to get a sense of Motto’s overall shape and potential. Vincent Morisset showed Michaels images and tests but took care not to give him any instructions. The idea, once again, was to let things steep and proceed through the fog, waiting for it to dissipate and for everything to clear up at the forest’s edge.

The constraints informing the literary work

Together with Michaels, the AATOAA team asked: what story should be told? In what format? With what tone? Should they go with a succession of independent short stories, like a series of podcasts, or imagine a single dramatic arc and a narrative divided into chapters?

The team’s reliance on the iterative method and a steady stream of back-and-forth discussions once again bore fruit. Vincent Morisset’s vision, Caroline Robert’s editing and imagery, and Édouard Lanctôt-Benoit’s technological discoveries informed Sean Michaels’ creativity, and vice versa. Everything AATOAA had imagined over the past year became a sort of constraint for the writer. The process was sometimes frustrating because the author didn’t have access to all of the tools in advance. So, he had to adapt and see what worked and what didn’t. As part of this process, an image sparked ideas for words and those words, in turn, inspired other images, and so the story was constructed, step by step. Marie-Pier Gauthier notes: “Sean tied all of the loose ends together and created the narrative thread that was missing.” And as Vincent Morisset explains, “the narrative thread determines the river’s direction and current.”

For instance, the decision to make the experience depend on the user’s circumstances was a guiding force for Michaels. The user’s location (in a kitchen, on a balcony, on the street and, more fundamentally, inside or outside) is pivotal to every prompt. Vincent Morisset explains, “the context and reality of the participants become part of the story.”

In the end, the editing experiments let the creators see the need to craft a single story. As they developed the prototypes, they realized it would be much more interesting for user videos not to appear in the program right away, but much later. Playing with time and anticipation opens up a stronger, sharper, and more poetic process of meaning-making. “The contributions of the users become, in a way, the project’s memory,” says Caroline Robert. “If we ask them to draw wind on a sheet of paper and send in their little clip, the image will take on a completely different meaning in another context, and it will be all the more surprising because the viewer isn’t expecting it.”

Memory images

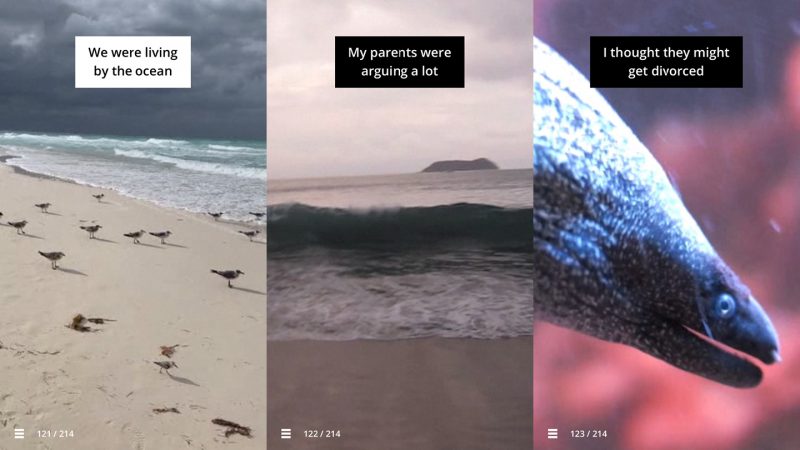

From these images and editing tests, Sean Michaels began to craft sentences. In the course of his scripto-visual experiments, he grew convinced that images could be seen as memories. In other words: “What you’re showing me reminds me of…” He later wrote on the NFB website: “The video snapshots people captured, even at their most raw and everyday, had a peculiar mystique. They seemed memory-like, or symbolic. Repeated clips seemed like a refrain.” (Sean Michaels, “Motto: Making Magic and Sharing Secrets.” NFB Blog, National Film Board of Canada, June 8, 2020, https://blog.nfb.ca/blog/2020/06/08/motto-making-magic-and-sharing-secrets/.)

The team decided that absence would be at the heart of the experience, which allowed the creators to get around the difficulty of constructing a narrative without knowing what images users will share from their environments—the images that will, in turn, act as words that intermingle with Sean Michaels’ narrative. The videos will therefore not refer to a presence or to a “here and now,” but will be interpreted as something that is already gone, much like photography and cinema, which were seen as a means of holding back time: the recording of a phenomenon, an object, or a face on film “immortalizes” it and saves it from oblivion. “You never really show what you’re talking about, you only suggest it, and, in so doing, you’re free to create meaning in unexpected ways,” says Sean Michaels.

Chapter 2, Fallen Star

The birth of the ghost

To tell a story, it’s usually useful to have characters who bring it to life. But the team quickly set aside the option of actors. If the narrator remains invisible, why not also introduce a main character that you never see? And, better still, why not make that character a ghost? “But without getting into the supernatural,” Michaels says immediately. “We needed a story where the presence of a ghost was normal, where you couldn’t question its validity or reality.”

My friend is a ghost.

They can walk through walls.

Their name is September.

The creators initially came to an agreement on these three sentences. But these sentences raised a fundamental question: what is the gender of the main character and how should Catherine Leroux, 2019 winner of the Governor General’s Award for translation, go about translating it? In English, “they” is neutral, but, in French, a choice must be made. Il or elle? Male or female? The authors don’t want to put September in a pigeonhole or influence the user’s relationship with the main character through their gender. Depending on whether people are male, female or non-binary, they won’t respond in the same way to a man as they would to a woman. Above all, Vincent Morisset wants people to be able to project themselves into the story, whatever their background, profile, or environment. Keeping the character gender fluid means that audiences will be more open in their emotional response. The team decides to embrace the random nature of the character: sometimes they will be a man, sometimes a woman.

And he or she will be called September. In Light Boxes, a strange and poetic tale by novelist Shane Jones, there is a spirit named February. Inspired, Michaels set his sights on September. “June and July felt like more feminine months to me and March felt more masculine. November is a bit on the dark side. September gave us the neutrality we were looking for and evokes something melancholic, like the end of summer.”

Encounters in Chile

Sean Michaels obviously brought a lot more to the table than simply finding a way to tie the images together. Most notably, he came up with the style and tone of the text. Vincent Morisset sums it up: “We had to find the right balance between being too playful and too heavy. We also had to inspire confidence in users. How do you get them into a mindset that’s open, generous, and curious to explore?” By multiplying the small literary experiences related to the images, Michaels became convinced that a light, mischievous tone would best suit the tone of the project. And because the team wanted to astonish and delight at every turn, he also knew that getting users to supply surprising answers to unexpected requests would be key.

Another important choice the team faced was how to address the audience most effectively. Finding the right fit was a long and difficult process but, in the end, Michaels opted for a pithy and precise style. The sentences are stripped down. They challenge. They disrupt. They are brief without being abrupt. The whole narrative is designed to be intimate, small, and astute.

In terms of the dramatic structure, chaptering a linear story demanded a lot of inventiveness. At every turn, the team had to come up with something new to drive the narrative, create suspense, keep the style fresh, and evoke emotions. “You can’t keep pushing the same buttons over and over again,” says Michaels. Knowing that they were going for a classic narrative structure (setup, conflict, climax, resolution) the team once again bounced ideas back and forth. That’s how they landed on the idea for chapter 5, “The Mind of September,” after staging the fight between the ghost and Motto, who is sad and angry after the “disappearance” of September.

Another important moment is the trip to Chile, in both Motto’s narrative and the team’s creative process: both are suddenly kicked into high gear. Chile impacts both the narrative arc and the project’s visuals. In the maelstrom of images the creators found swirling around on the web (the famous “rabbit hole”), they came across a giant hand reaching up out of the Atacama Desert. This impressive sculpture by Mario Irarrázabal became the cornerstone of the overall structure and led to a film shoot, “a kind of pilgrimage” for Vincent Morisset. In the Chilean desert, Morisset shot footage—hands and keys that get lost in the sand—that would become fundamental set pieces for Motto. Between fantasy and realism, this hand—with fingers that rise into the sky, aerial but firmly anchored to the earth—feels like at once like a ghostly mirage and a confrontation with a very tangible reinforced concrete block. It became the site of key encounters: primarily between the narrator and the main character, but also between the creator and the project, and maybe between the story and the audience too. It’s a pact of sorts, like shaking hands to make a bet or a promise.

Guiding and reassuring

The first few minutes of a film are crucial for audience buy-in. The same is true of a book: often the opening lines reel the reader in and get them to commit to the whole. In Motto, too, something special—and key to the success of the experience—is at play in how the first of the six chapters is written.

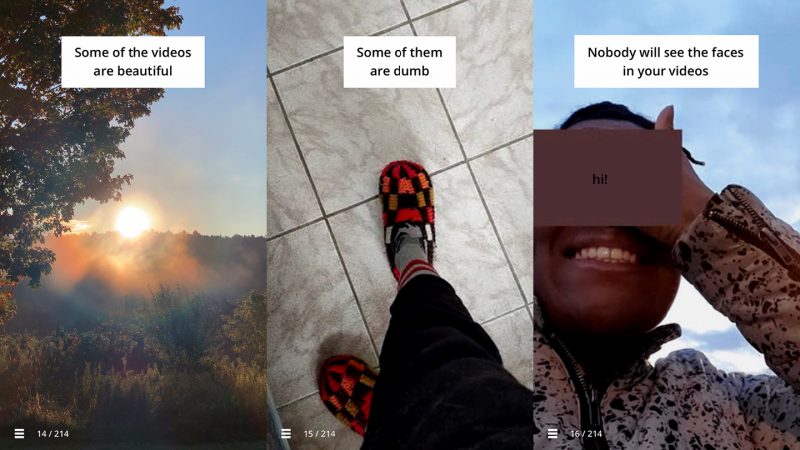

The team decided to guide the users gently in the introduction, to take them by the hand so that they get the most out of Motto and understand its stakes and participatory nature. The hook could have been stronger or more disruptive, but the team might have run the risk of losing the audience en route. Caroline Robert adds: “We had to reassure everyone and make it clear that we weren’t expecting ‘beautiful’ contributions or speaking to an audience of ‘artists.’ Forget the performance and feel free! That’s one of the reasons why the first images are quite raw and commonplace, the kinds of shots that we can all take on our phones.” It was a wise choice to ensure audience participation would be relevant and so nurture a new form of interactivity.

4. The search for “organic” interactivity

Playing with audience participation in an interactive project is always a strange challenge. In Vincent Morisset’s words, it’s “an absolute puzzle.” How do you motivate people to participate? What do you offer in exchange? What satisfaction will the user get by investing in the work? How can you encourage them to come back? What is the driving force behind their commitment?

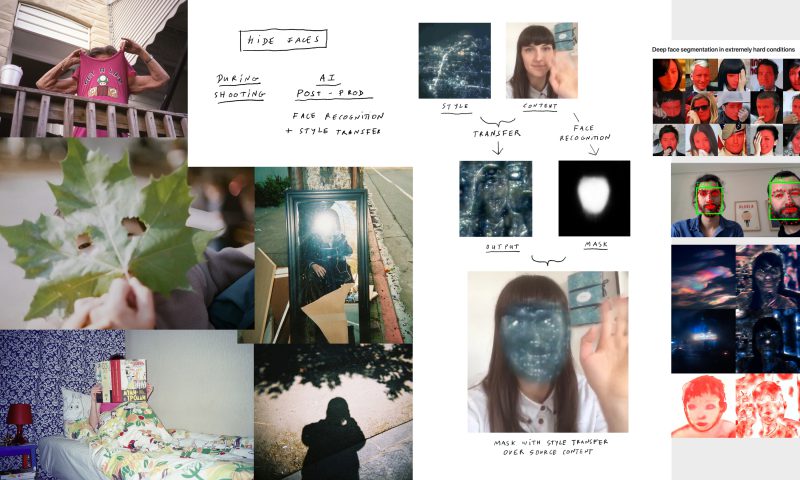

Anonymization and universal content

With the ever-increasing reach of social networks and the heated debates on personal data that often follow, people are more cautious than ever when they go online. It was therefore necessary to reassure users of Motto’s good intentions and establish trust. That meant anonymizing all of the content provided by users. Take a picture of yourself, and a box will cover your eyes. Though Édouard Lanctôt-Benoit had dreamed up all kinds of other special effects, this one proved to be the most effective—and playful: they could write on the box! In addition to reassuring the user, this feature is also immediately understandable.

Thus reassured, the user’s attention must then be captured and maintained—meaning that all users must be addressable, whoever they may be. That was the beauty of BLA BLA and the success of Way to Go. It’s also the essence of the web as a language: the universality (of content and uses) contributes to the success of works that transcend cultural barriers. That’s why Motto is called Motto. The project’s code name became its title for at least two reasons: it makes sense in both French and English and because it “speaks” beyond words through its sonority and graphics. “Like the project, it’s a bit of a chameleon,” says Vincent Morisset.

Similarly, there is no sound or intonation in Motto—and yet we have the feeling that a small voice is whispering in our ear. There are no recognizable faces. Instead, there are images that are evocative, whether you live in Montreal, Tokyo, or Marrakech. This universality of the textual and visual address makes it possible for the entire planet to take part in the project. It’s worth recalling that this accessibility is one of the missions of a public service like the NFB, and, while the creative process is experimental, the end result is not. This “small” work has the ambition to be as big as the global audience that it addresses.

Chapter 2, Fallen Star

Intimacy

That said, the most obvious answer to hooking the user ultimately lies in the form of Motto itself. First of all—and this is almost a luxury—everyone can consume it at their own pace, like a book that you pick up and put down at your leisure, delaying its completion as you see fit. And secondly, because the kind of interaction that Motto invites is very specific in nature.

Motto requires real participation from the user: a physical and intellectual effort, small journeys, research, and discoveries. The stated ambition is to offer “cerebral” interactivity, to put users in a particular state of mind that is conducive to the experience. It’s not about inviting them to engage with content or an interface. They have to give something of themselves, invest themselves, and be imaginative and inventive. The program gives back by replaying the images they have shared. And when users see their own shots appear on the screen, they become all the more attached to the experience. The game becomes a joy, a personal delight.

This feeling of intimacy, derived from the technological device that is physically closest to us, provokes emotions and invites users to reflect on things as fundamental as human nature, the joy of life, the passing of time, and memory. It exhorts them to revisit everyday life, to see it differently and to draw inspiration from both the beautiful and less than beautiful things around them.

This creates a dialogue between Motto and the user. A bond is created, because the program reveals itself as attentive and caring, considerate and curious—in a word: generous. It addresses us as users directly, invites us to carry out actions akin to an unveiling or even an undressing. In return, we offer something that belongs to us, to those around us—under the cover of anonymity, of course. And little by little, a friendship forms.

Vincent Morisset evokes “intimacies that feed a shared story.” And he’s right: the appearance of our images in the program fosters the feeling of (co)constructing a habitable and desirable universe together, as a group of three, and more broadly of creating a (virtual) community of equals—as though all of these intimate fragments could build a collective memory.

What participation?

This “instantaneous archiving of realities intertwined with fiction” is what matters most to Motto’s creators. They had no specific quantitative expectation of audience engagement, and today they marvel at each contribution, which they accept “as a gift.” All of the videos uploaded to Motto are, of course, subject to a regular and manual curation of sorts. Some are permanently added to the image bank that initially seeded the project, while others are only visible to their authors. Users play the game, with some returning again and again, and come to the process with the authentic and generous state of mind so sought after throughout the creative process.

The authors and producers conceived and built this project to last over time. As the months pass, a sort of aggregated documentary will continue to emerge that will ultimately inform us about our era. There is no doubt that the abrupt appearance of masks in our daily lives will be as visible as the changes in season or the variations of light.

In a context where social media platforms are specifically designed to prevent Internet users from breaking free of them, Motto also proves that it’s possible to imagine something different, to create other uses for these platforms. “And when people get out of the lake and come into our river, they see that the water is fine,” says Vincent Morisset with a smile.

Motto pushes its own boundaries

They say that to change the world, you have to first change the way you think about it. And the world definitely changed in the spring of 2020, but only three lines of text required tweaking to take into account the global confinement of almost half of humanity caused by the coronavirus pandemic. The proof, if any was needed, that Motto had good aim and hit the mark.

With this new work, which grows richer with every visit, AATOAA engages us in a collective reflection on the meaning of existence in our current troubled times. And Motto is such a lively work that it sometimes even spills over from its original creative medium. Chance led the creators to invent a “live” reading of their work first at the Electric Dreams Festival in the UK in the summer of 2020, and then at the Festival du nouveau cinéma in Montreal in the fall of the same year, with upcoming exhibitions also in the works. As with the team’s previous attempts to broadcast online programs in real time, the experience led to a revisiting of the work in the form of a new choreography. Sean Michaels read the text (sometimes assisted by someone else for the French version), Caroline Robert operated the mobile device, Édouard Lanctôt-Benoit managed the technology, and Philippe Lambert composed the accompanying music. Inspired by the practices of Twitch, their live reading gives us the chance to travel through someone else’s eyes and smartphone and fosters both a new way of seeing and a new way of relating to our devices.

So, to answer the question that we asked ourselves at the beginning of this article—what is Motto?—Vincent Morisset answers that it is “a magic box that things go into.” You put what you want in and, with the ultimate gift of divine freedom, you also get the meaning that you want out. The project also engages something of ourselves—our homes, our neighbourhoods, or our environments—and in so doing, we share something dear to us with other users. This small window onto the world creates a palpable link between fellow human beings and connects us to others from our own intimate spaces. And, in the end, it’s this feeling of sharing—and the joy of having shared—that inhabits us at the end of the experience. Coupled with the desire, no doubt, to encourage our loved ones to join in the beautiful dance of images imagined by the creators. Motto is most definitely a free and open work for free and open minds, one that gently whispers to us: “Life depends on how you look at it.”

0 comments