by Beyza Boyacioglu

Empire: The Unintended Consequences of Dutch Colonialism by Eline Jongsma and Kel O’Neill is a documentary project that one may encounter as a video installation, an interactive website or an artist’s book. For four years, the filmmakers followed the ghosts of The Dutch East and West India Companies in ten different countries, chasing the human-scale traces of colonialism. What they were after was not a post-colonialist grand narrative but what was hidden in corners and gray areas that could only be brought to surface by the soft touch of oral histories (Jongsma & O’Neill, 45). The result is an “exploded feature film” as they once called it; with each shrapnel carving a unique shape as they land.

Background: Historical and Personal

In 1602, the Dutch government sponsored the creation of a chartered company named The Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, VOC) by granting it a 21-year monopoly in the Asiatic spice trade. It is considered the first true multinational corporation organized as a shareholder company. VOC enjoyed government-like powers such as waging war, colonizing countries, imprison or execute convicts, and issuing money of its own. Until it became defunct in 1796 and nationalized, the company sent almost a million Europeans to Asia, some of whom made East Indies their home.

Nineteen years after VOC was established, Dutch West India Company (Geoctroyeerde Westindische Compagnie, GWC) was founded to carry out Atlantic slave and sugar trade between West Africa, Brazil, the Caribbean and North America. It was given a 25-year monopoly in the parts of the world that are not in VOC’s control. The company continued its operation until 1792 when it was acquired by the Dutch government and its colonies were brought under direct rule of the state.

In the former colonies of VOC and GWC, legacies of the two companies are still visible in the form of twisted ironies or cyclical narratives. In Empire, Jongsma and O’Neill document how the social conditions created by the colonizers did not disappear but were mutated over time and passed down to new generations in various forms. Their personal histories are also affected by the unintended consequences of imperialism.

In the Empire book, Jongsma recalls a memory from Indonesia when a Sumatran man compares his skin color to hers, finding it funny that the tone of their colors match. In Indonesia, Jongsma is a ‘Bule’ (foreigner) despite the fact that she, very visibly, inherited her Indonesian grandmother’s genes. She then reminisces about growing up in The Netherlands not resembling her own mother who looked like a Viking. Such irony is visible within many stories of Empire.

Another personal account from the book is about O’Neill’s parents who met in Vietnam during war. His mother was a nurse and his father was a hospital administrator. “In the grim arithmetic of foreign intervention, I am a remainder” writes O’Neill in the book and continues: “So too are many of the people who we have filmed for Empire, from the Dutch-descent Jews of Sulawesi to the children of Orania’s true believer Afrikaner separatists. Some might call them villains, but I think they deserve some measure of our understanding. I share a place beside them, as many of us do, on the wrong side of history” (Jongsma & O’Neill, 66).

Sinister Humanists

The inception of Empire goes back to Jongsma and O’Neill’s time at the Theertha International Artist’s Collective’s New Media Residency. The first day of production yielded an outline of the larger project. They began their shoot at The St Nikolaas Home for Burgher Ladies where unmarried and widowed Dutch-descendent women reside. Once a privileged colonial middle class holding high bureaucratic positions throughout Dutch and British rule, Burghers today are a disappearing population. Sri Lankans have mixed feelings about the Burgher women since they embody the colonizer for them. One of the Burgher women puts it bluntly: “I don’t think they’ll miss us”.

- Scout images of Burgher ladies

As the audience, we are touched by warmness and humanity in the Burghers’ portraiture in Empire, yet we cannot shake off the darkness in their history. This emotion is a recurring theme that Jongsma and O’Neill exemplified in the Burgher ladies story. In each narrative of Empire, we are overwhelmed by having to judge the subjects for ourselves. Perhaps one can see the interactive form (both the installation and the website) as a physical/visual manifestation of this burdening freedom.

- First “map” of Empire: Migrants (3 feet by 7 feet)

- Empire: Migrants Final Cut Timeline

Empire The Installation

Jongsma and O’Neill initially envisioned Empire as a video installation with numerous satellites orbiting across platforms such as a website, a blog (http://sinisterhumanists.tumblr.com), a book, and additional online content. “This scattered approach reflected the complexity of the subject matter. Limiting our work to one platform and one voice didn’t seem like the right way to examine (post) post-colonialism. We needed to allow for multiplicity of perspective, and to reflect the far-reaching impact — in both geographical and spiritual terms — of the Dutch colonial endeavor” (Jongsma & O’Neill, 8). They decided that it is okay for a viewer to casually stumble upon one portion of the work and never realize that it is a part of a larger project. They were just going to lay out breadcrumbs.

- Poster of the installation at Jogja National Museum in Indonesia

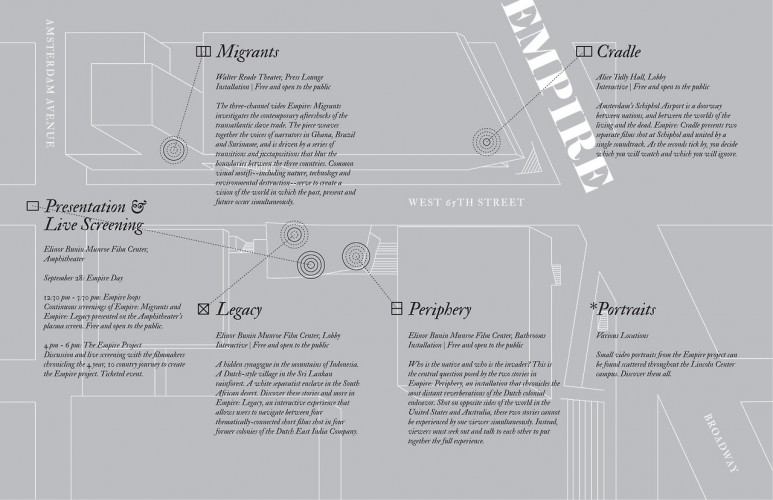

The core installation mirrors this approach in its design. The piece consists of four chapters: Cradle, Legacy, Migrants, and Periphery. The branches were spread out in various venues of Lincoln Center during its world premiere at 51st New York Film Festival’s Convergence program. Multiple channels within a physical space allow for playful spatial arrangements. Jongsma and O’Neill see “movement as an interface”. They say that video installation is the most immersive form available today, even more so than virtual reality since it does not require wearing a headset.

- Map of Empire at NYFF

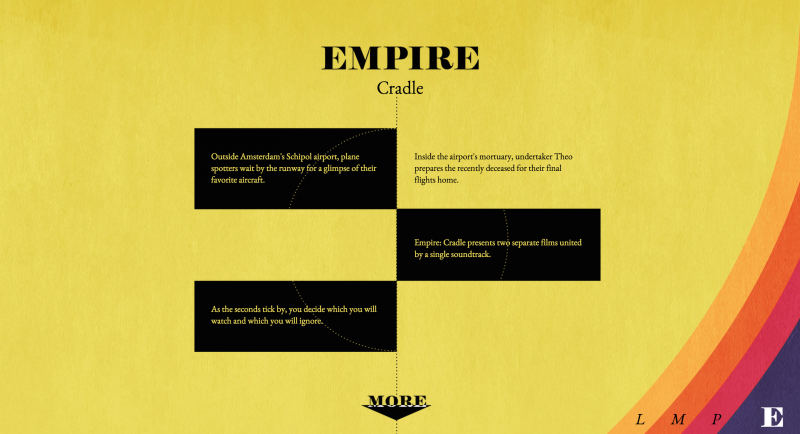

“Cradle” consists of two videos from Schipol Airport in Amsterdam: A South Korean adoptee watches planes take off through his binoculars, while a man working at the airport mortuary prepares a deceased immigrant’s body to be sent off to his/her homeland. Questions regarding the place one calls home tie the two stories together, in addition to the two channels’ shared soundtrack. What is the significance of a birth place if you have lived your whole life somewhere else? What does being buried in one’s homeland imply for an immigrant?

“Migrants” is a three-channel video piece that deals with the residue of GWC’s transatlantic slave trade in Ghana, Brazil and Suriname. Stunning cinematography is accented by a spatial montage of three images; so much that at times the viewer forgets that they are looking at something as eerie as an interbred Dutch community in Brazil where it is hard to tell people apart. Other stories include runaway slaves who created a new society in the rainforests of Suriname and Ghana’s Fancy Dress Festival where the locals dress up as former ‘European masters’.

- Migrants from NYFF

- Migrants from IDFA

‘Legacy’ is composed of four split-screen videos, looking at VOC’s reverberation in the East Indies. A Nazi reenactment group in Indonesia and a whites-only community in South Africa are some of the darker bits of the wrong side of the history. The viewer is free to wander around looping videos which makes it challenging to grasp the larger picture. Difficulty in connecting the dots is well-suited here since we attempt to piece together an unwieldly imperial masterplan.

- Legacy from NYFF

- Legacy from IDFA

‘Periphery’ is perhaps the most playful one of the four installations. One of the two characters in this section is an Indonesian actor who lives in the US and is only offered Mexican roles based on his looks. The second one is an Australian Aboriginal biker who suspects he might have descended from the exiled VOC sailors. Two channels were available in the restrooms of Lincoln Center; men’s and women’s bathrooms each offering a different version of the story. Unless you can pass for both genders, you must hear the other side’s version secondhand or not at all.

- Periphery from NYFF

- Periphery from NYFF

- Periphery from NYFF

Empire The Interactive Web Documentary

In order to unpack the design decisions behind the web documentary, it is important to remember that Empire was initially created as a video installation. Each section of the i-doc translates the mechanics of a spatial arrangement and its affordances into two dimensional space, plus interactivity.

The web version of ‘Cradle’ imitates the spatial quality of the installation: two channels share one soundtrack and you can flip back and forth between two videos by hovering your cursor on a different position.

- Empire i-doc ‘Migrants’

‘Migrants’ is presented as a three channel video identical to the installation. The viewer is devoid of the freedom to click around and see different parts of the story, which could have been simply implemented in the web version. Instead, when one completes the loop, an unexpected reward is unlocked: you can download the three channel video for your private, random access viewing. A graphic diagram, which appears when the cursor is placed over the video, reveals the country that is being spoken about.

- Empire i-doc ‘Migrants’

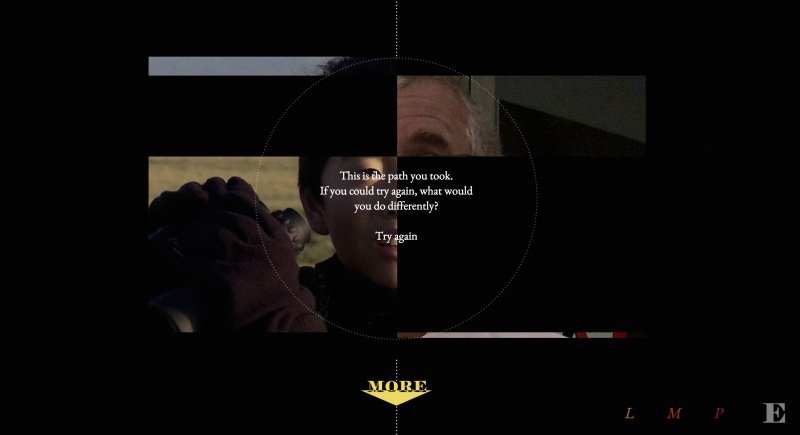

Four split-screen videos in ‘Legacy’ play all simultaneously. When you are watching one channel, you are missing the other three as it would be in a video installation. Each viewer follows their own path and unravels shared themes between four stories. At the end of this section, one can even Skype the filmmakers to discuss the connections they have seen.

- Empire i-doc ‘Legacy’

In ‘Periphery’, there are two videos on top of each other, one being inverted and its soundtrack tuned down. Parallelism between the two narratives is highlighted by their synced montage and musical cues, and complementing compositions.

- Empire i-doc ‘Periphery’

Jongsma and O’Neill decided to translate the installation into an online platform, initially for practical reasons. Even though a video installation offers an immersive and one-of-a-kind experience, it has limited accessibility due to its sculptural nature. On the other hand, web is tailored to a larger audience. The filmmakers decided to take part in POV’s Hackathon, collaborate with a team of programmers and explore how the physical form of an installation can be adopted to a virtual one. The prototype created at this hackathon can be viewed here. Experimenting with the dynamics of a website prompted the filmmakers to reconfigure the way we view videos on the web and challenge the usual ‘click and play’ format.

A conventional interactive platform applies methods of user experience design in order to improve usability, efficiency and user satisfaction. Jongsma and O’Neill test this rule and ask: Who says the experience has to be easy? In Empire, the purpose of interaction is not ease of use but rather its contribution to the story and the explored theme. The viewer might need to make some effort to unravel the meaning behind an interaction, similar to how we might have difficulty grasping the significance of two consecutive shots in a film. Empire does not refrain from challenging how we experience videos on the web and how we consume interactivity. In fact, the filmmakers do not really care for the so-called ‘impact’ of their web presence. They do not wish to measure the journey of the audience in units of engagement; as in how many times we click and where. Quantifying everything actually flattens out the artistic voices and conversations, they say.

Empire’s cinematography, editing, installation and interaction design all come together to create great finesse. One last portion of its craft that calls for mention is its graphic design which was heavily inspired by western esotericism. The filmmakers liken the way Empire sets up systems to manage large amount of information to the cabalistic tree that attempts to sort out the creation and continuation of the universe. The overlaying of a circle and a square is a recurring image inspired by the freemasonry symbol, square and compasses. The graphic elements in Empire allude to a networked world where scientific thought and the occult, spirituality and the natural universe are all interconnected and affect each other.

- Empire i-doc

- Empire i-doc

- Moodboard for the i-doc by Clint Beharry

Empire The ArtBook/Travelogue

Jongsma and O’Neill say that each medium they explored was born out of a reaction to a limitation. The transition from installation to the web spreads the piece to a wider space thus a larger audience, whereas the book allows Empire to endure over time. In their talk at Tribeca Storyscapes 2015, they mentioned the Chrome web browser updates as one of the challenges of working with an online platform. As the book marks the end of their four-year-long journey, they know that it will stand the test of time regardless of what happens to the intangible online content.

- Empire book

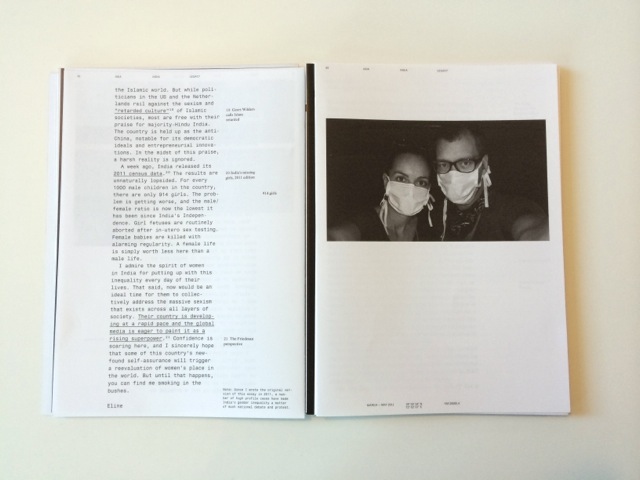

Empire, the book, offers essays on the history of VOC and GWC and the communities affected by their activities, personal entries by the filmmakers, behind-the-scenes photos, video stills, interviews, descriptions of installations, and even a diary of the POV hackathon. The design of the book toys with the graphical conventions of written text; similar to the way the i-doc teases online video protocols. The chosen font implies the tone of the narrative, whether it is an intimate story or a historical revelation. Each page is annotated with the geographic coordinates of the mentioned city, name of the country, continent and the section of the documentary (i.e. “Africa, South Africa, Legacy”), still images, keywords and playful phrases (i.e. “tantalizing possibility” or “Quranic chant”), and also online links.

- Empire book

- Empire book

“Empire is a monster that has eaten our lives. This book is an attempt to kill that monster” says the duo. They did kill the giant monster and moved on to new projects. Soon, we might come across Jongsma and O’Neill’s work in virtual reality and smartphone platforms.

References

Jongsma + O’Neill, The Unintended Consequences of Dutch Colonialism. 2014.

0 comments